- JohnWallStreet

- Posts

- Sponsorship Equity Is the Hook for Big Brands in Challenger Sports

Sponsorship Equity Is the Hook for Big Brands in Challenger Sports

sports. media. finance.

Editor’s Note: The JohnWallStreet IQ Q4 ‘26 State of the Media Union (a virtual call) is slated for December 3 at 430pm EST. We’ll talk through the biggest developments over the last 90 days and their impact on the rights landscape moving forward. JohnWallStreet media consigliere Patrick Crakes and former Fox Sports president Bob Thompson will lead the interactive conversation.

Interested in joining our exclusive intelligence quorum? Reach out to Corey Leff at [email protected] for more information (including annual membership costs). You’ll be smarter and better connected for it.

Sponsorship Equity Is the Hook for Big Brands in Challenger Sports

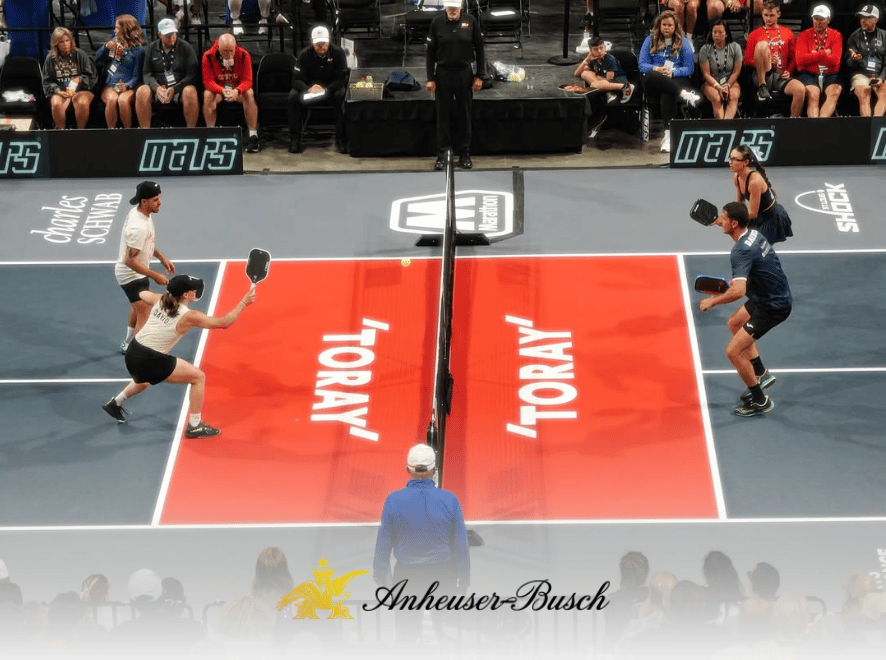

Anheuser-Busch (NYSE: BUD) bought a Major League Pickleball team, the Atlanta Bouncers, in November 2022. The press release announcing that investment stated the company would consider the ‘Sponsorship Equity’ model with other emerging sports where its sponsorship, marketing, and scale could help spur a league or team’s success.

That logic made sense. Sponsors tend to overpay early-stage rights owners for their marketing assets, and those dollars often help to keep the property afloat. Blue chip companies will also drive awareness and attract other partners.

“There should be some financial upside for the brand investing,” Nick Kelly (CEO, Encore Sports & Entertainment) said.

But the publicly traded brewing company hasn’t taken an equity stake in any challenger leagues since. Neither have any other CPG, apparel, or lifestyle brands.

That is despite the slew of leagues to have emerged and the value of MLP teams having risen from <$1mm to $16mm over the last three years.

It seems like a missed opportunity. These properties need a credible champion behind them.

And as a brand partner, “you want the real tangible upside nowadays because ROI is being far more scrutinized and eyeballs and impressions alone never pencil out when you're starting with such a small fan base [as is the case with most emerging teams/leagues],” Kelly said.

While CPG, apparel, and lifestyle brands have sat on the sidelines, there are several examples of media companies investing in challenger sports leagues within the last half decade (see: Fox and UFL/IndyCar or ESPN and PLL).

The structure has gained steam because it has become increasingly clear it is a ‘win-win’.

“If the media partner, which has inherent amplification opportunities, feels like it has upside in the success of the league, the value of the incremental investment it makes to ensure the property is successful, versus just being another rights package, is significant,” Kelly said.

Fox doesn’t work to simply turn a profit selling ads against UFL content. It promotes the league, probably beyond deserved levels of amplification given the audience, in an attempt to drive the property forward.

A blue-chip brand partner could authentically integrate itself into an emerging league and deliver similar value from a promotion and activation standpoint. The company would presumably come with a larger and more diverse audience, and its commitment would indicate support for and confidence in the property, which should open doors to new non-endemic partnerships.

It signals they trust the team or league to “drive their brand and value the audience it brings to them,” Kelly said.

Third-party validation is often necessary for challenger properties to attract mid-sized and smaller brands, and to sell the CFOs within those companies on spending despite their relatively small audience size.

It’s difficult to see the ‘Sponsorship Equity’ model working within tier one leagues. Valuations have gotten too high and the ownership groups are too mature.

But leagues lower down the value chain, who are seeking to gain legitimacy and improve their product, should be receptive to selling equity to a top brand.

“If they’re investing, they’re going to [ensure] a first-class experience,” Kelly said.

Large companies can also provide valuable operational support and expertise.

“A lot of emerging sports properties struggle to do the basics; marketing, social, digital, ticket sales,” Kelly said. “An [established] brand could come in with the resources and an army of people to do all that literally on day one, either internally or with external agency partners, and it’s a rounding error for them. It takes a long time for teams to stand that kind of support up, especially in these small leagues.”

There is seemingly little downside in a challenger rights owner taking on an equity investment, outside of a discussion that must be had on category exclusivity. Eliminating a valuable sponsor vertical can make it difficult for numbers to pencil out at the team level.

The challenge is more likely to come in the form of finding companies that want to invest outside their core expertise and take on the responsibility of operating a sports property for an extended period.

“You’re not going to be looking at this like a PE firm planning to exit a big four team stake in five years,” Kelly said. “This is very much [going to be] a long-term investment.”

Both in terms of realizing its financial upside and converting fans of a niche sport into supporters of the brand.

“Your investment in trying to pull these new audiences will only pay off once they see you are there as an authentic champion of the property,” Kelly said.

And that takes time.

Reputational risk is the greatest concern on the brand side.

“If the upstart league goes upside down, or they have issues, like a labor dispute, you’re going to be pulled into it,” Kelly said.

And it’s not as if startup leagues have a long track record of success.

But that should dissuade marquee brands looking to spend sponsorship dollars in a challenger sport from taking an equity interest.

“It’s your fiduciary responsibility as a company to what is best for shareholders,” Kelly said. “If you're investing in something that you believe is going to have a future, but there is no potential upside for your brand, that’s charity.”

CPG brands are best suited to adopt AB’s ‘Sponsorship Equity’ model.

“They can drive scale and awareness overnight,” Kelly said. “They can take the property into thousands of retail stores; they have hundreds of millions of customers.”

And a seven-figure investment should be do-able for a company with a $75mm+ annual sports marketing budget (think: top ~50 spenders).

The rub is going to be that most of those companies have market caps in the hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars. Investments in assets unlikely to move the needle are often viewed as a distraction.

Large organizations willing to make these kinds of investments tend to have a venture arm.

“They typically invest in endemic assets and technology or services partners that support their core business,” Kelly said. “But a lot of them are increasingly starting to look at mar-tech and different ways of validating innovations and reaching new customers. A sports property could fall in that category.”

Highly capitalized challenger brands seem most likely to pursue the equity route with an emerging property.

It’s a “way for them to stand out,” Kelly said. “It’s kind of like the old Red Bull model.”

Who will make the next move into team/league ownership remains to be seen. But AB isn’t going to be the only consumer-facing brand invested in sport come 2030.

“The years of throwing money at everything and if the property blows up the only thing the brand gets in return is increased sponsorship spend are over,” Kelly said.